DHTech on Django

Our December meetup was focussed on discussing the Python-based Django framework, since we knew a number of members of the community use it for their projects and others might be interested in either using the framework or adapting approaches and ideas from it for their own work.

The meetup was attended by seven people with quite a range of experience with Django: some have used it extensively, others are maintaining legacy projects, others have only a little familiarity with it. Here’s what people commented when they answered the introductory question: what do you use django for, if you use it at all?

- Using Django for legacy projects, but not the first choice (because of programming language).

- Using it for a number of large database driven web applications (CDH @ Princeton).

- Not used it, know of it.

- More familiar with smaller apps, Flask; learning, starting to appreciate precision; toying with using Django architecture in Jupyter notebook - Python for data science vs web dev.

- Discovered Django in a hackathon, started using it for all projects at Haverford; started introducing Fast API. Working with student developers, it was easier to rely on what they already know about Python instead of having to learn the Django approach; also have inherited a number of Django projects, many Django cookie cutter sites, that need maintenance.

- Number of larger db-driven projects, web projects; some use Django REST, some use GraphQL with React or Vue frontend for projects that need to be interactive. Also use Django templates when applications don’t need interactivity. Most projects are in Django, new projects all go into Django. Also have Rails and legacy PHP applications, but trying to standardize on one framework (DARTH / Harvard).

- Only a little direct exposure; used a different Python framework from the 2000s (Zope), still has that code around. Main website & project sites using Drupal, starting to use some Django things, seems like a nice environment, especially if you start from the database. Interested to learn if that’s true, hear more about experience, especially maintenance for the long term.

A couple of people had some specific things they wanted to share, but there were also a number of questions and conversations around what was shared, and other pain points or things they wished they could do with Django.

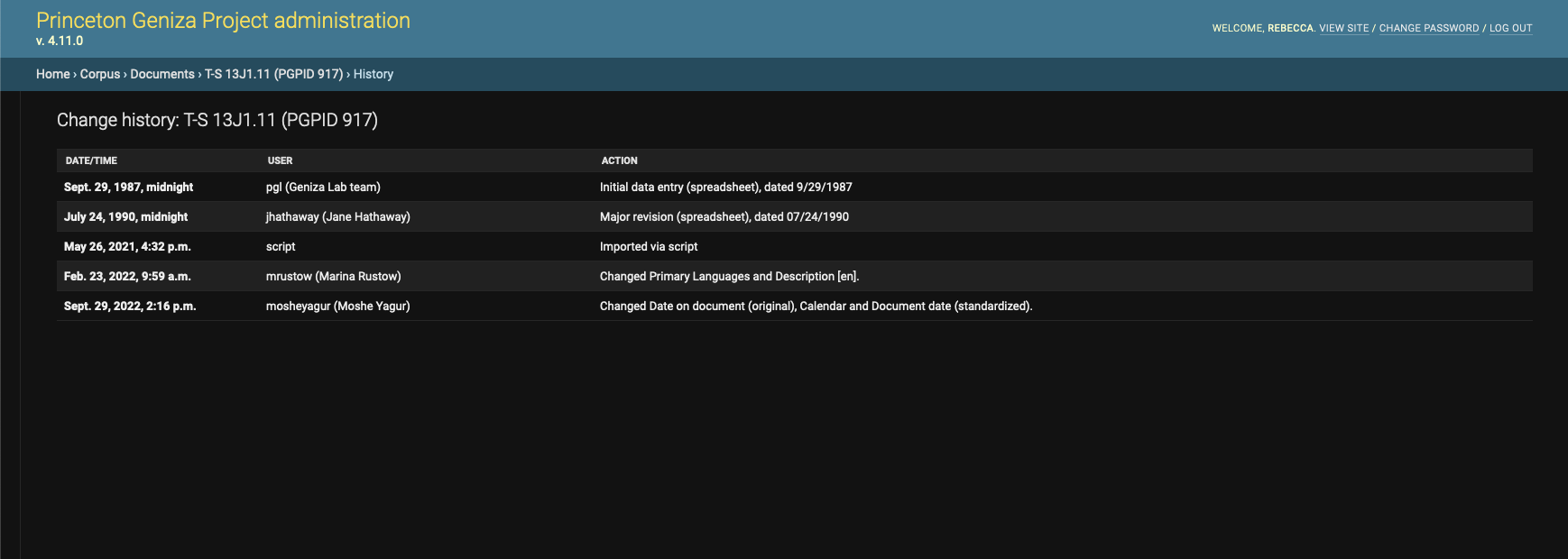

Rebecca Sutton Koeser (Lead Developer at the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton University) shared a few tips and best practices they’ve adopted for their projects at Princeton. For instance, if you’re using Django Admin for data management and data entry, you get the benefit of automatic log entries that track who edited which records when, and in newer versions of Django there’s a structured notation that indicates which fields on the record changed. At Princeton, they’ve leveraged this to create log entries for other events — whether scripted migrations done in bulk, or documenting record history from other systems before the Django database existed. Their approach is to write a migration that creates a “script” user and then write code to generate log entries when appropriate in migration scripts.

Screenshot of the Django Admin history for a document in the Princeton Geniza Project showing entries for record creation before the current database existed, scripted import into the database, and edits since then

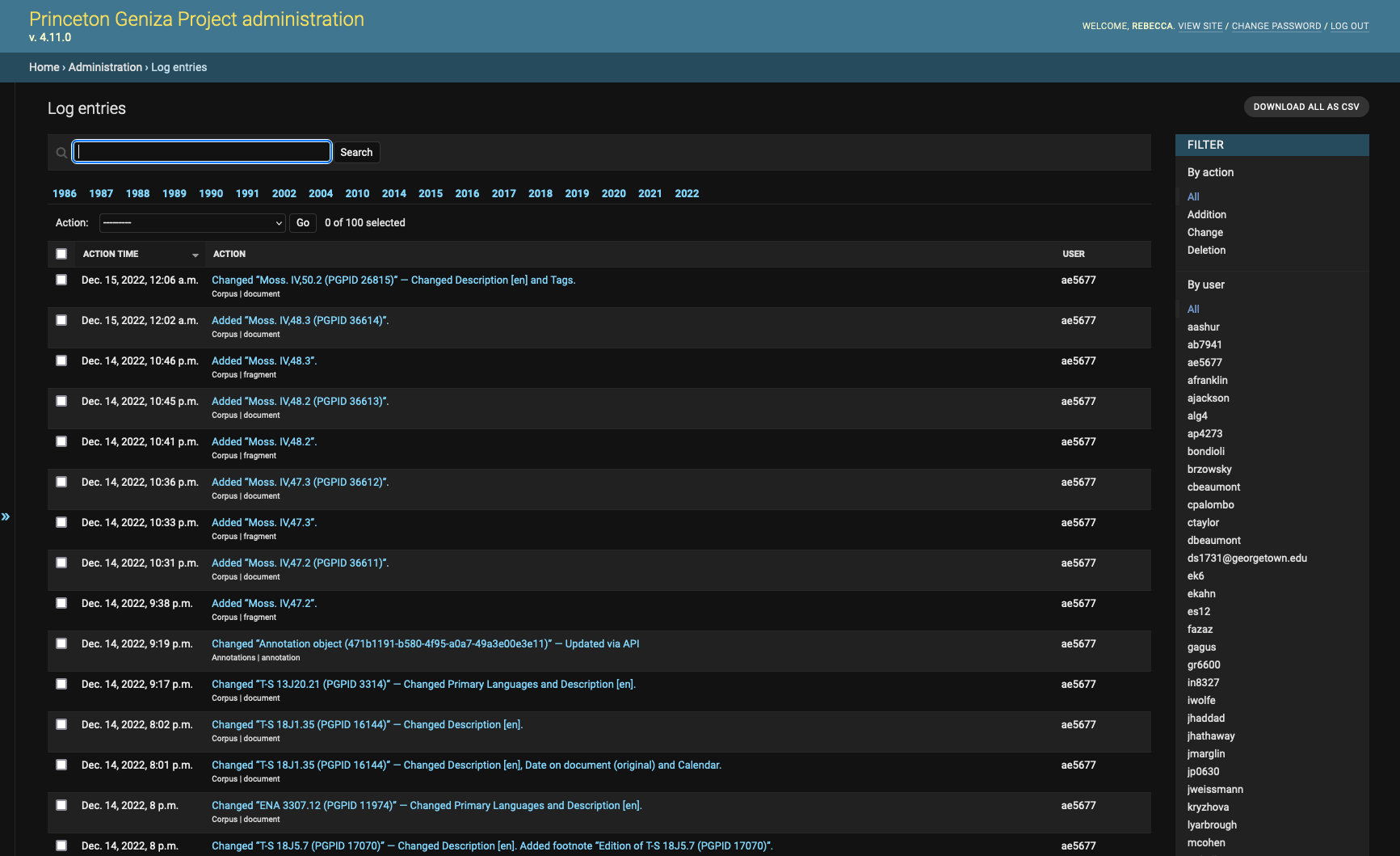

In parallel with this use of log entries, there’s a small Django application (django-adminlogentries) that you can install to easily view log entries in the Django Admin interface, which can be really helpful to see what work has been done recently, what changes were made by which person, reporting on activity in the database, etc.

Screenshot of the Django Admin log entry list view on the Princeton Geniza Project.

Julia Damerow (Lead Scientific Software Engineer, Arizona State University) asked if this is versioning or just logging. One of the projects she works on uses django-simple-history for versioning. It keeps track of the changes done to objects and allows you to roll back to previous versions. Julia was curious if Django’s built-in logging mechanism could be used for this kind of versioning as well. It looks like, however, the logging mechanism is not a true replacement for django-simple-history (at least not without additional work).

Another approach that was discussed is to create custom modules for common tasks used across applications; the most simple and successful one is pucas for standardized login using Princeton’s CAS authentication. Cole Crawford (Software Engineer, Humanities Research Computing, Harvard University) chimed in that they have something similar at Harvard (django-harvardkey-cas). Robert Casties (Research Scholar, Research-IT, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science) asked about reusable modules and how they are structured. Rebecca said that you can take an app or module built as part of a Django project and extract and generalize it for reuse, and that the Django documentation is really helpful: there’s a tutorial on how to write reusable apps.

Rebecca also shared how they have implemented exports to make some of the information from the database available in CSV format. Admin users can export all or a filtered subset right from the admin interface, but they also have a cron job that synchronizes the CSV files to a data repository on GitHub (for example, see https://github.com/princetongenizalab/pgp-metadata with data exported from Princeton Geniza Project). This will be the basis for dataset publication, but it also makes the data available for viewing, filtering, and downloading with GitHub’s Flat Viewer.

For automated database documentation, at Princeton they are using DBML (Database Markup Language), dbdocs.io, and django-dbml to generate documentation and diagrams directly from the Django models. For example, see the diagrams for the Princeton Geniza Project database and the GitHub Actions workflow used to generate and update the database documentation. There was some brief discussion of the related tool, dbdiagram, which uses the same DBML notation to design databases (see this diagram from the Geniza project).

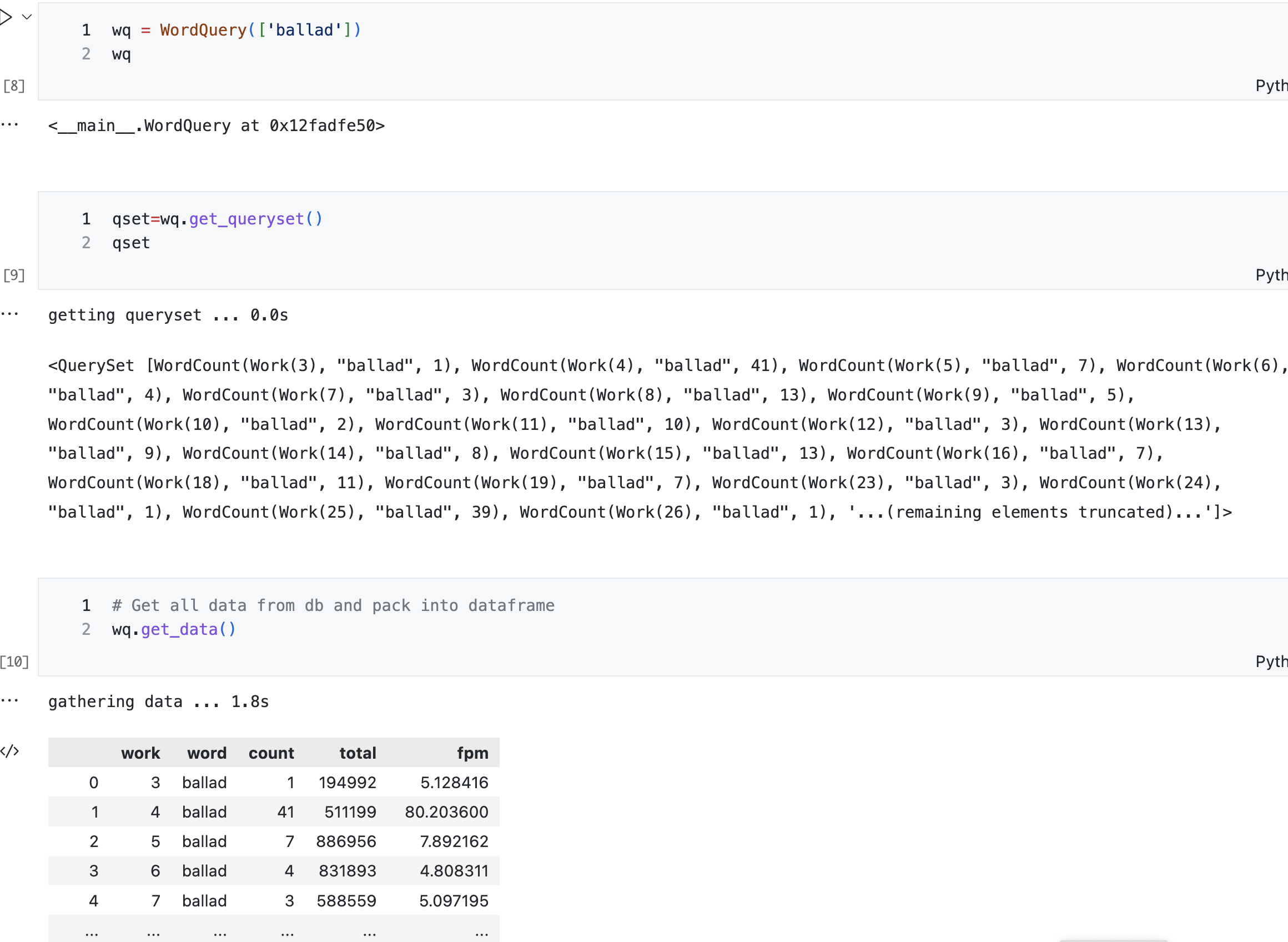

Ryan Heuser (Research Software Engineer, also at Princeton with Rebecca), shared about his experiments and ideas for connecting Django and Jupyter notebooks. He said that he usually works with tabular data in CSV files or similar, which doesn’t provide the relationships available in the Django models; often the data doesn’t have the structure and validation that we have in database records (e.g. years that aren’t guaranteed to be integers).

Using Django models in Jupyter.

Ryan showed a solution he found that lets Django play nice with Jupyter so you can access querysets and models in a notebook. This way you get all the structure and native field types from the models. You can define arbitrary methods and attach them to existing objects to give them new behaviors, e.g. taking a Princeton Prosody Archive HathiObject and adding a method to get the full text. This behavior might not be needed for the web interface but it is powerful for analytical work.

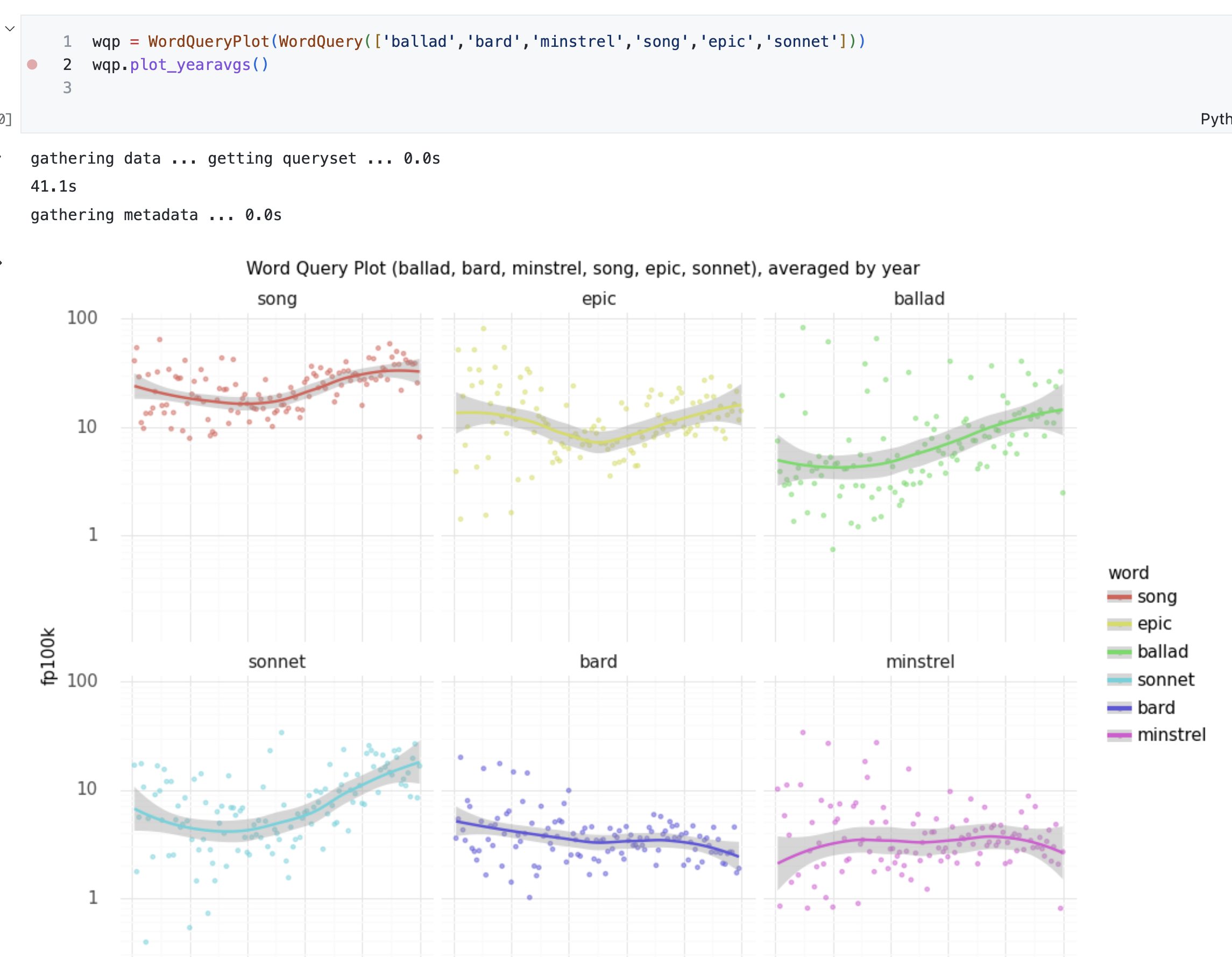

Plotting Wordqueries

Similarly, this kind of notebook integration allows you to graph data quickly in cases when you don’t want to build a web interface or a view necessarily, but simply want to see the data in a Jupyter notebook. In the notebook Ryan presented, he experimented with ways to store token counts in Django and quickly get statistics for any word across the texts. Ryan’s conclusion was that it is cool for experimenting in real time, but it’s kind of fragile. How can it be made more stable? What if I wanted to use it in Colab? This little Django hack might not work, and it’s also a lot to expect someone else to insert this weird async unsafe configuration.

Julia interjected that in neuroscience there is a data standard called “Neurodata Without Borders” (NWB). Part of it is an API with reference implementations in Python and Matlab. The libraries allow you to create objects with predefined properties describing data such as experiment design, experimental subjects, behavior, and the like. Julia thought that it would be amazing to have something similar for humanities with a predefined data model that allows you to capture information relevant to humanities projects that might not be available in standard repositories (e.g. author identifiers, affiliation identifiers, software used to create a dataset, etc). She said she loved the idea of using Django like Ryan presented, and suggested that one could create a library like NWB that would empower this kind of work.

There was some discussion of how to package project data for others to reuse, since none of us are going to let someone use Jupyter to access our actual production database. Ryan shared an example from his Literary Language Toolkit (LLTK) project, which has methods to download several available text corpora. You could imagine doing something similar to download an app and an exported version of the database so that you could work with a local copy. Andy Janco (an RSE in the Research Data and Digital Scholarship group at the University of Pennsylvania) suggested Huggingface Datasets as a great way to share and version data. He also commented that he’s a fan of installing iPython so that the built-in Django console acts kind of like a notebook. He shared a link to an article describing how to use Django with Jupyter. Robert commented that SQLite could be a nice solution for sharing data like this, and said that if you have control over the source data and code and can generate the exports, this would be a nice approach. Although if you generate exports in other formats, then the CSV is guaranteed to be clean, too. Rebecca said this sounded somewhat analogous to the “baked data” approach, where static data is deployed as part of the application along with the code.

Julia commented that usually their projects don’t have data in a format where they can easily use the Django models; a lot of times it’s just text or xml. She wished there was a code library or utility that would make it easy to iterate over all the texts with metadata, store it in a database, and then maybe on top of that, there could be a Django model that works with the same data structure. Then you could either use the library to index the data and make it findable, maybe with an elasticsearch component; then, if you’re building a webapp, you can plugin and use the data right away.

Julia then changed the subject and asked a question about difficulties with maintenance. She said their projects have lots of plugins and dependencies, and they regularly get Dependabot alerts about new versions that encourage updating. But much of the time, if you just update, nothing works. They have similar issues with Java projects, but 80% of the time it’s fine; it’s only occasionally that you need to pull the code down and do more work to get the upgrade to work. On their Django apps, a lot of the time the PR checks fail, and they have to pull the code down and review to address manually. There was some discussion about this, and it seems that everyone deals with some amount of this difficulty, although perhaps more painful for some than others, and worse in some environments than others (e.g. Javascript vs.Python), and a few people reminded us of the below xkcd comic along the same lines. Andy shared a link to Django Packages, and said that it was sometimes useful for comparing and assessing packages.

It was a lively and productive discussion that filled the full hour of our scheduled meetup and even spilled over to Slack with some follow up conversation. It sounds like there is potential for the DHTech community to collaborate on tooling and approaches (maybe something to work on in a future hackathon!), as well as other common frameworks and technologies that we could share best practices and learn from each other. Some of those topics include internationalizing applications in Django or other frameworks, or indexing and normalization for search on non-english text, e.g. transliterated Arabic.